Enabling RLM Inference with Shared Program State

RLM inference comes for free in programming systems using shared program state.

Jan 20th, 2026

Two recent lines of work have revealed revealed the benefits of marrying LLMs with programming environments, such as a Python REPL. Recursive Language Models (RLMs)[1] automates the work of managing long prompt contexts using by enabling LLMs to self-decompose context prompts.Also, our recent paper on shared program state[2] enables LLMs to modify the program state of a host program through a controlled interface. The common pattern of using an LLM for automated state management means programs using shared program state can easily use RLMs.

In this blog post, we show how to enable the RLM inference strategy in only a few lines of code in a program with shared program state.

What are Recursive Language Models?

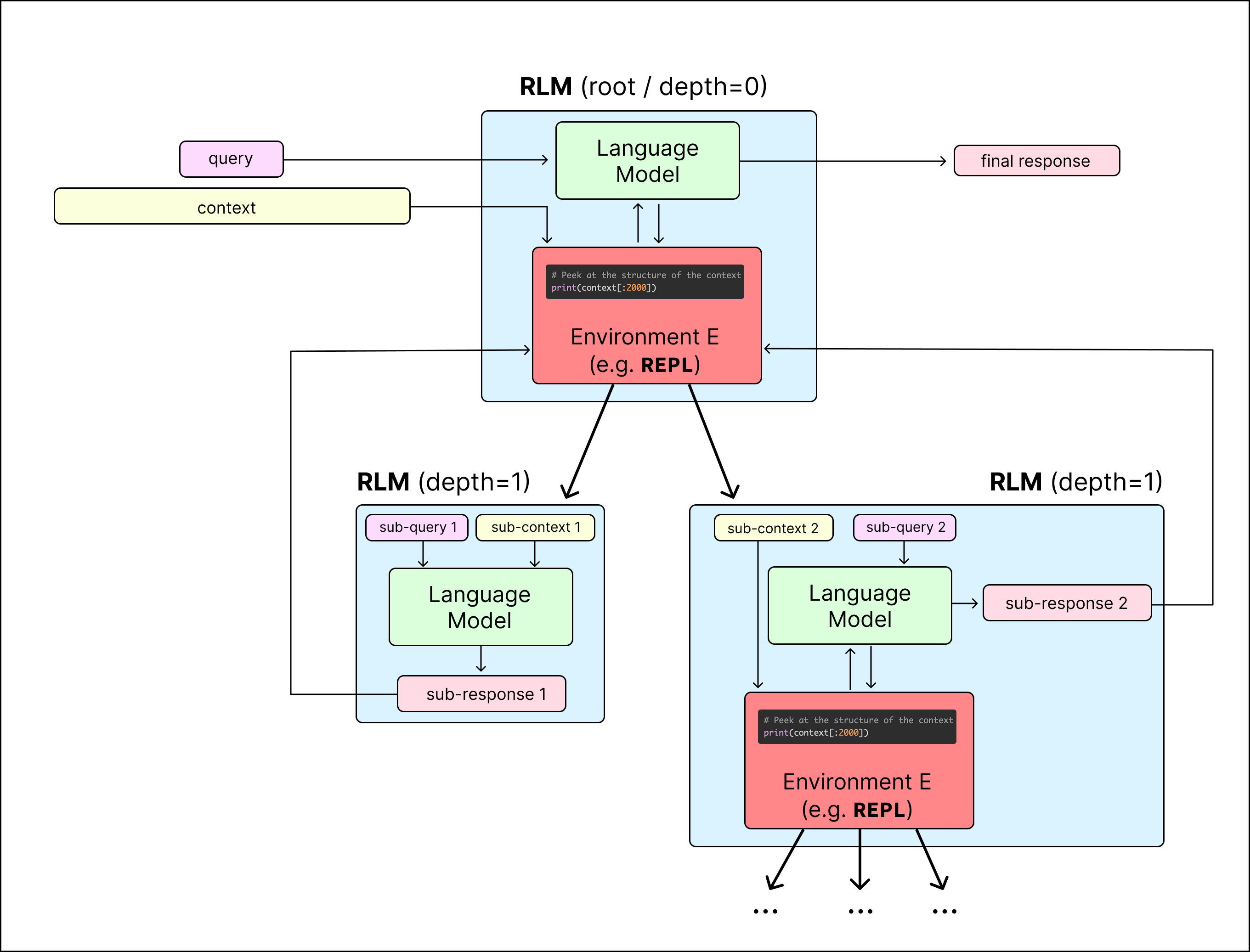

An RLM leverages the LLM to automate context management. The LLM uses a Python environment to manage its context prompt and the context prompts of recursive sub-LLM calls. The LLM issues Python code to view portions of the context, programmatically parse contexts, perform Python-based computations, and/or compose contexts for sub-LLM calls.

In short, enabling RLMs consists of enabling:

- LLM-driven context management, and

- Recursive LLM calls.

The key insight here is that enabling RLM means enabling a limited form of shared program state, particularly in which the LLM uses Python and recursive LLM calls as its interface language to the state.

Enabling RLM in Programs with Shared Program State

We will explain how RLMs comes for free in programs with shared program state by an example program using our Nightjar library. The example is a program for executing the trec_coarse split of the OOLONG[4] benchmark, which was used in the RLM work[1].

The trec_coarse benchmark requires answering queries about (potentially large) datasets of questions associated with user IDs and dates, provided as a string dump. The queries ask about a semantic label for each question (but the dataset does not contain explicit labels).

Below is the program written using Nightjar:

import nightjarpy as nj

@nj.fn(config=nj.configs.INTERPRETER_PYTHON_NESTED_JSON_CONFIG)

def oolong(context, question):

"""natural

Look at <question>, and <context>. Save the answer to <question> as <:answer> as a string in the

format specified in <question>

"""

return answer

That’s it! Let’s go over each component of the program.

The decorator @nj.fn enables inline natural code using a triple-quoted string with the natural language identifier. Natural code blocks can be embedded anywhere Python statements can go, including within for loops, nested functions, with blocks, etc.

@nj.fn takes a configuration object for adjusting natural code execution settings, such as the base LLM model, the max number of iterations allotted for the agent, the agent system prompt etc.

Python variables that the LLM executing the natural code can read are denoted as <var> in the natural code. Python variables that the LLM must write by the end of the natural code execution before switching back to the Python runtime are denoted as <:var>.

Nightjar enables shared program state: the embedded natural code has direct read and write access to the program state (the variable scopes, the heap, and the control state) of the program that the natural code is embedded in. In this example, the natural code automatically reads the question and context Python variables and writes a string value to the Python variable answer, that can be used after the natural code like any other Python variable.

How does Shared Program State work?

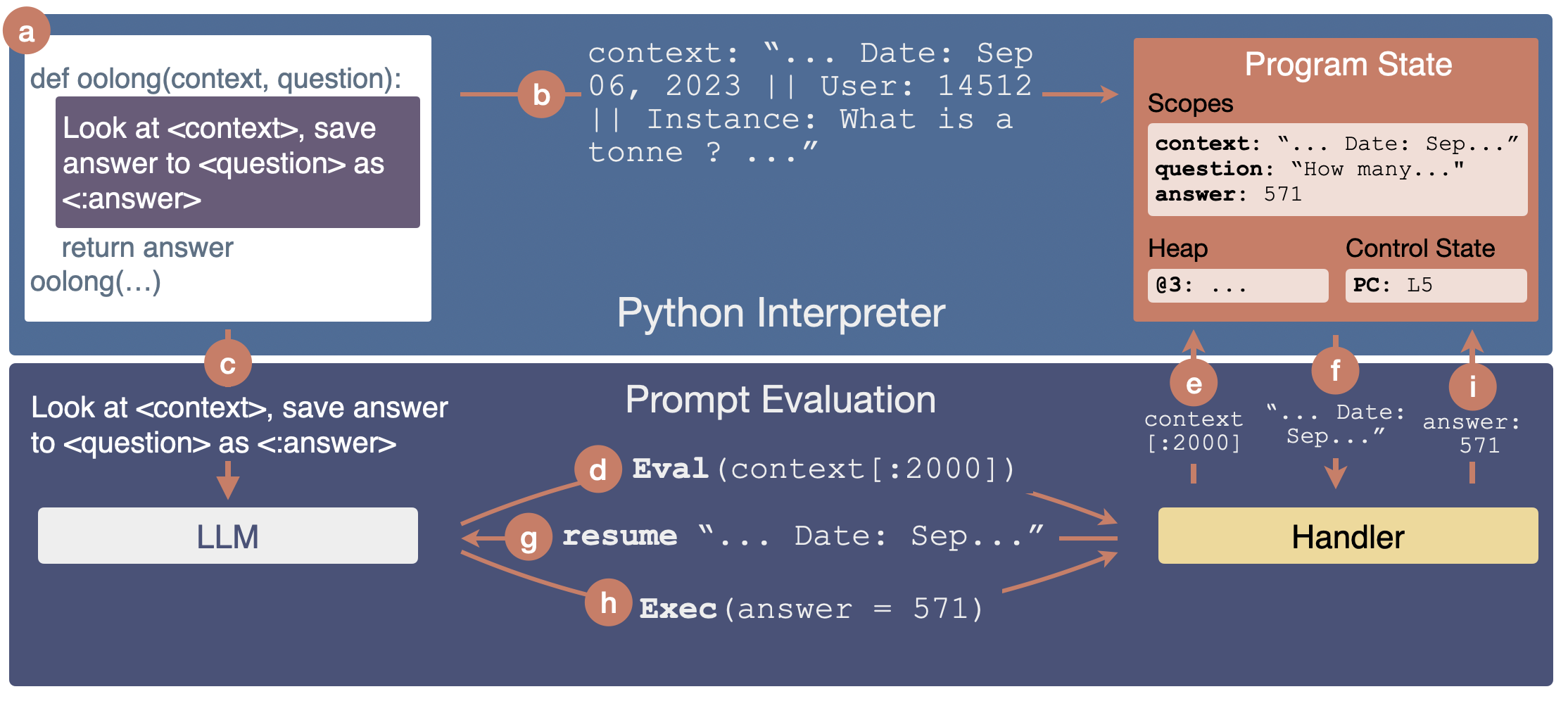

Shared program state is a programming abstraction that offloads the work of managing LLM call inputs and outputs within a host program.

For example, in the figure above, (a) the program using shared program state first executes as normal in the host system. (b) the function call makes the variable assignment for the function argument context. (c) Then, the host system hands execution control to the LLM. The LLM issues effects to interact with the program state. Here, (d) the LLM issues a Eval request to read the first 2000 characters of the context string. (e) The handler resolves these effects by interfacing with the host program state: (f) The handler reads context from the shared variable scopes. (g) The handler resumes natural code execution with the retrieved value, and the LLM continues the agent loop. (h) the LLM issues another request Exec, to assign the variable answer to the integer 571. (i) the handler updates the shared variable scopes accordingly.

Using shared program state, the embedded LLM agent directly reads/writes program variables, manipulates program data, and implements control flow in the program. The LLM agent issues effects, which are distinguished requests of services to the host program; handlers, implemented in the host system, dispatch these effects with respect to the host program state. In the above example, the LLM agent uses a specialized DSL (domain specific language) as effects. Other designs are also possible, such as using Python code. We defer additional details of enabling shared program state to our paper [2]. With the paper, we also released the Nightjar Python library that enables shared program state for natural code in Python programs.

Evaluation

We evaluated the above program to show that using RLMs through Nightjar achieves parity to the official RLM implementation.

Methodology

We evaluated the tasks with context window length of 131k, following the RLM paper[1]. We also follow their experimental setup to use GPT-5 with medium reasoning effort as the root LLM and GPT-5-mini with medium reasoning as the sub-LLMs and to set recursion depth limit to 1. We ran the benchmarks for N=3 runs and report the mean and standard deviation of metrics across runs.

We compare the performance of the following methods:

- LLM: Direct GPT-5 query with entire context prompt.

- RLM: The official RLM library with GPT-5 root LLM and GPT-5-mini sub-LLM.

- Nightjar: Ablation using Nightjar with GPT-5 and with recursive LLM calls disabled. The LLM agent still has access to the program state (and thus the context in the program state).

- Nightjar (RLM-Enabled): Nightjar with recursive LLM calls, thus enabling RLM, with GPT-5 root LLM and GPT-5-mini sub-LLM.

Results

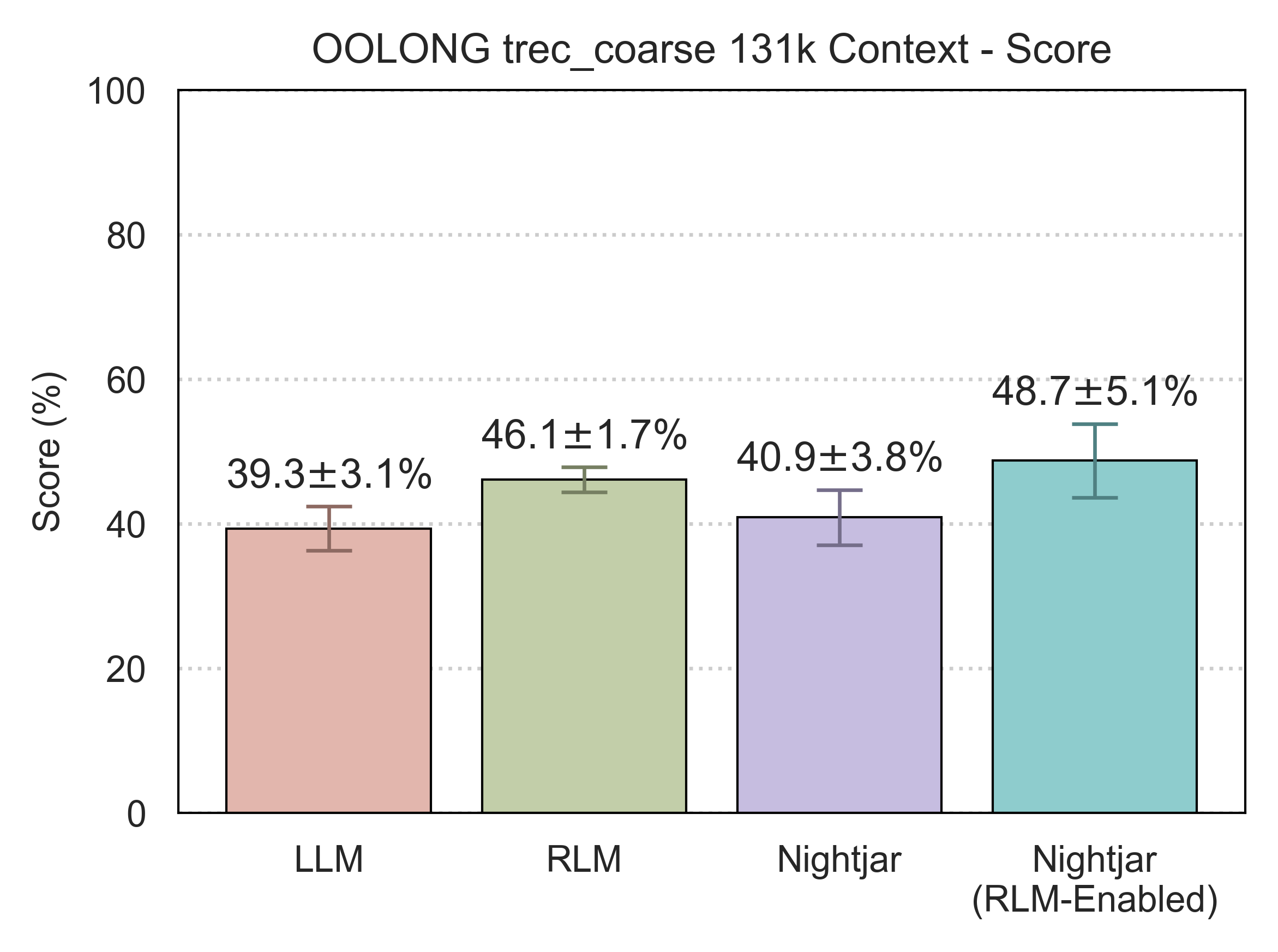

As shown below, Nightjar (RLM-Enabled) achieves a slightly higher score to RLM, demonstrating that using the RLM mode in Nightjar is a competitive alternative to using RLM via the official implementation. The Nightjar ablation without recursive LLM calls achieves comparable score to the base LLM, but performs worse than RLM and Nightjar (RLM-Enabled). This demonstrates that the agent setup does not significantly result in accuracy improvements, but the recursive LLM calls does boost accuracy.

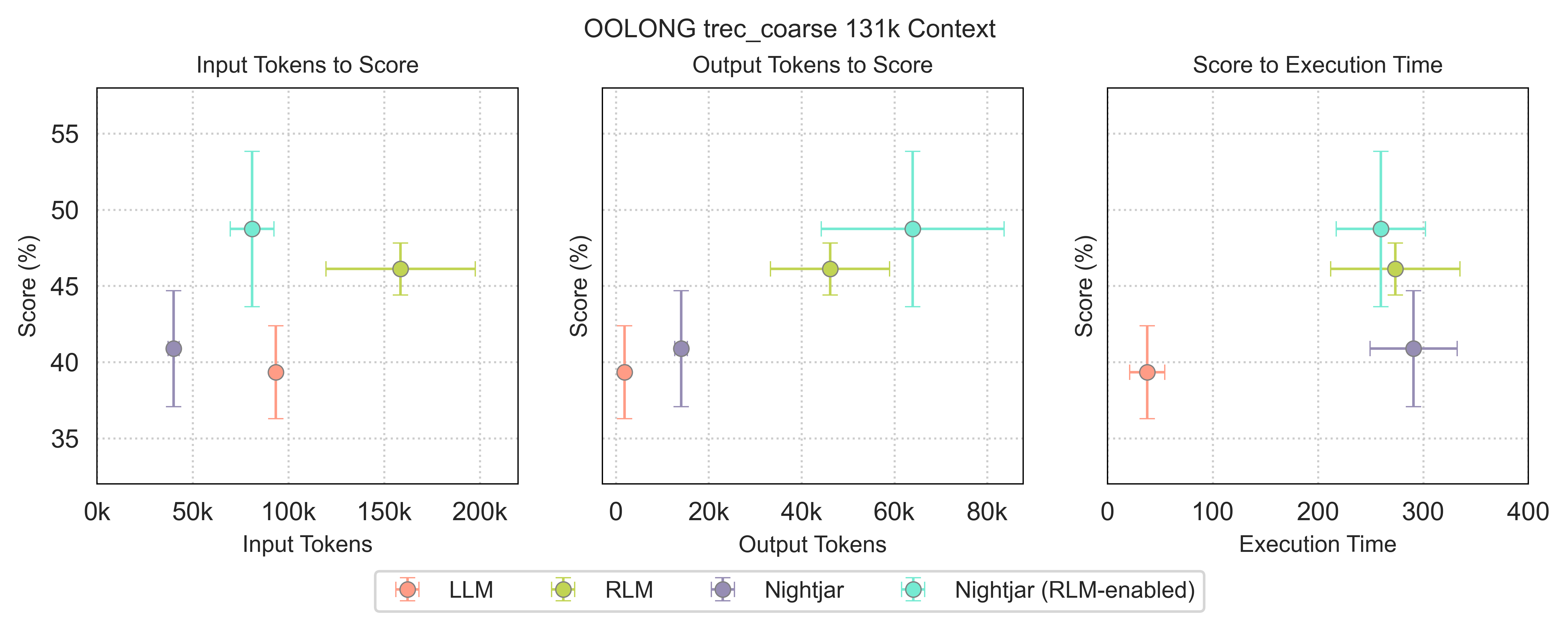

Below are plots comparing input tokens, output tokens, and execution time of using each method. The y-axis shows the score.

RLM uses the most input tokens, while Nightjar (RLM-enabled) uses the most output tokens. Notably, the base LLM uses more input tokens than Nightjar and Nightjar (RLM-enabled) but has the lowest score. This shows that LLM in Nightjar and Nightjar (RLM-enabled) can manage the context efficiently.

Nightjar (RLM-enabled) has similar execution time to the official RLM implementation. RLM, Nightjar, and Nightjar (RLM-enabled) are 6.9-7.7x slower than using the base LLM as they rely on an LLM agent.

Using the RLM inference strategy in Nightjar is a comparable to using the official RLM implementation on tasks like the above, where the context is represented as a long string of data. Nightjar also provides other benefits when writing programs, such as using natural code to implement control flow and to manipulate program data structures such as lists and objects, because it enables shared program state. See our paper for more details.

Note on Safety

As with most software using LLMs, Nightjar should be used cautiously. In other programming systems and libraries that enable LLM usage in programs with isolated program states, the programmer is in full control of what the LLM sees and writes. Shared program state gives some of this control to the LLM in exchange for automation and abstraction. Nightjar employs some safety mechanisms to safeguard LLM hallucinations such as by restricting variable accesses and variable writes to those denoted in the prompt. See our paper[2] for more details on the safety measures.

We also recommend running Nightjar programs in a container just in case.

Roadmap

There are still a lot of new features and performance improvements planned for Nightjar and shared program state. Some of which are:

- Interface Designs: Nightjar is designed to be easy to hot-swap and to extend with new LLM to program state interface designs. Different designs results in different accuracy and runtime and are suited for different applications. For example, using Python with and without LLM calls are two different execution substrates with different performance profiles. Nightjar currently supports three designs: A custom DSL, Python, and Python with LLM calls. We are continuing exploration of new designs to improve program accuracy and runtime. We welcome contributions from the community for new interface designs.

- QOL: We plan to release some quality of life extensions for syntax highlighting, linting, etc.

- Safety Mechanisms: We are exploring different strictness levels of safety mechanisms, such as type-checking, and invariant checking.

Stay tuned for more improvements to Nightjar.

Closing Remarks

Nightjar and shared program state is not the end to the challenge of regaining high-level abstractions when programming with embedded prompts. Nightjar and shared program state reduces the friction when using embedded prompts in formal programs, but there remains a lot of complexity when when programming in natural language with prompts in general due to issues in LLM robustness and interpretability. We hope to see more works in reducing complexity when programming with prompts while retaining gains in robustness and interpretability.

Citation

@misc{cheng2026sharedstaterlm,

title = {Enabling RLM Inference with Shared Program State},

author = {Cheng, Ellie Y. and Weber, Logan and Jin, Tian and Carbin, Michael},

year = {2026},

month = {January},

howpublished = {Blog post},

url = {http://elliecheng/blog/2026/01/20/enabling-rlm-with-shared-program-state/}

}

References

- Amanda Bertsch, Adithya Pratapa, Teruko Mitamura, Graham Neubig, and Matthew R Gormley. Oolong: Evaluating long context reasoning and aggregation capabilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.02817. [link]

- Ellie Y. Cheng, Logan Weber, Tian Jin, and Michael Carbin. Sharing State Between Prompts and Programs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.14805. [link]

- Alex Zhang and Omar Khattab. Recursive Language Models. [link]

- Alex L. Zhang, Tim Kraska, and Omar Khattab. Recursive Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.24601. [link]